Table of Contents

Introduction

The objective of this article will be to assist you in understanding what a balance sheet is, what is presented on the balance sheet, the importance of the statement of financial position as well as some other topics that will improve your foundational knowledge of the balance sheet. Fundamental analysis of the balance sheet is an exciting topic that will be discussed in a future post.

The four basic financial statements include the balance sheet, income statement, statement of cash flows, and the statement of retained earnings. The IRS does require every incorporated company to maintain a balance sheet and an income statement. The exception to this is that sole proprietorships and partnerships are not mandated to prepare a balance sheet, it is optional for them, but useful for the business.

Some other common names of the balance sheet used in practice include the statement of financial position and the statement of financial condition. Aliases for the income statement include the statement of profit or loss, P&L, statement of operations, and the statement of earnings.

Purpose of a balance sheet

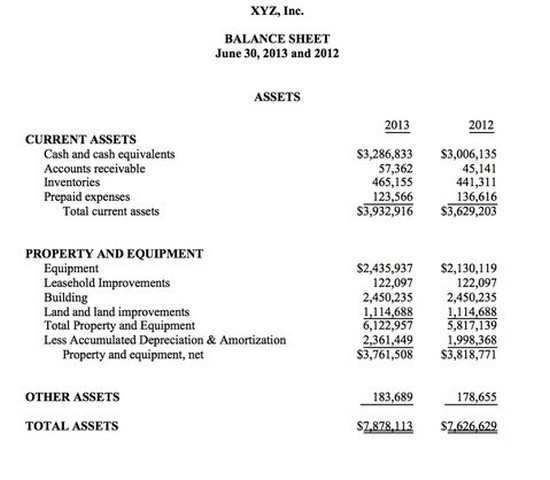

The balance sheet provides a snapshot in time of a company’s assets, liability, and equity accounts. The image below is a comparative balance sheet that compares the Balance sheet on June 30, 2013 to the Balance sheet on June 30, 2012. A comparative balance sheet is a useful tool to assess progression and see if the company is growing.

The core function of the balance sheet is to provide interested parties an idea of the company’s financial position at a specific point in time to assess their performance. These interested parties include current and potential investors, creditors, suppliers, government agencies, labor unions, and competitors.

All of the interested parties noted above will examine the assets, liabilities, and equity and compare these figures to industry averages to assess company’s performance and see if they want to conduct business with the company.

One of the most important things to understand about a balance sheet is that is must balance. What exactly must balance?

Assets = Liabilities + stockholders’ or owner’s equity

you may hear about the famous abbreviation “ALOE” in your accounting courses that represents this equation. All of our assets (debits on the left) must balance with our liabilities and stockholders’ equity (credits on the right).

Business owners utilize the balance sheet to get a glimpse of and assess the health of their organization. There are a multitude of ratios that can be utilized from balance sheet data that allow us to assess liquidity, solvency, and efficiency of the company and compare it to previous periods to see if the company is improving or declining in these areas over time.

Assets

As noted above, assets are anything with value attached to them or a resource of value that can be exchanged for cash. Some assets may also have the ability to provide cash flows in the future. An example of one of these assets may be a piece of machinery that is used in the manufacturing of a product, which is then sold and exchanged for cash after completion.

Tangible vs. intangible assets

Assets can be either tangible or intangible. Tangible assets are any assets that are physical and can be touched. These include but are not limited to cash, vehicles, inventory, buildings, equipment, investments, and land. Intangible assets are not physical in form and include but are not limited to copyrights, patents, trademarks, customer lists, goodwill.

Current assets vs. noncurrent assets

A balance sheet will also distinguish between current and noncurrent assets (also known as fixed assets). Current assets are assets that the company plans to use or sell within one year from the reporting date.

Some current assets include cash, cash equivalents, accounts receivable, marketable securities, prepaid expenses, and other liquid assets. Current assets play an important role for the company because they can be utilized to fund day-to-day operating expenses of the business.

Noncurrent or fixed assets are any asset that is not expected to be consumed or converted into cash within a year. Another common name for the section of noncurrent assets is property, plant, and equipment (PP&E).

Some examples of fixed assets are machinery & equipment, office furniture, company vehicles, buildings, and land. Usually, companies have a capitalization policy, which is a specific amount where any fixed assets purchased that cost less than that amount are expensed and any amounts over that amount are capitalized or depreciated over their useful life.

For example, if the capitalization policy were $5,000 and some furniture cost $5,600 and had a useful life of 7 years, the furniture would be capitalized and depreciated at $5,600 / $7 = $800 per year. Land, on the other hand, cannot be depreciated because it cannot be depleted over time unless it was a piece of land containing natural resources like minerals, trees, water, oil, etc.

Depreciation of a tangible fixed asset is regarded as depreciation. Similarly, depreciation of an intangible asset is referred to as amortization. If a fixed asset has stayed in operation to the end of its useful life, it is typically disposed of by selling it for a salvage value. A salvage value is the amount the company expects to receive in exchange for the asset at the end of its useful life.

Some assets may become obsolete because they stop working or there is no longer a market for them. These obsolete assets may be disposed of without receiving any money for them. In this case, the asset is written off the balance sheet as it is no longer in use by the organization.

Asset ordering on the balance sheet

Assets are ordered based on their liquidity in descending order from most liquid assets to least liquid assets. Liquidity is measured in how long it would usually take to convert the assets into cash. As such, cash is listed first as no conversion is needed. Marketable securities would be second in line as it would take a few days to convert them to cash.

Accounts receivable follow marketable securities as these amounts will be converted to cash based on the company’s normal credit terms or conversion may be expedited through factoring the receivables (selling receivables to a company).

Inventory may come after accounts receivable depending on the industry and how quickly the inventory is turned (received and sold). After inventory is fixed assets as PP&E are more expensive and are used in operations for a longer period of time.

There is generally a smaller market for PP&E relative to the inventory being sold. Last would be an intangible asset like goodwill as goodwill is only converted to cash when the company is sold.

Liabilities

Liabilities on the balance sheet represent something that the company owes. Liabilities can be decreased through payment like paying off debt, from providing a service for unearned revenues, or through the transfer of goods.

Current vs. noncurrent liabilities

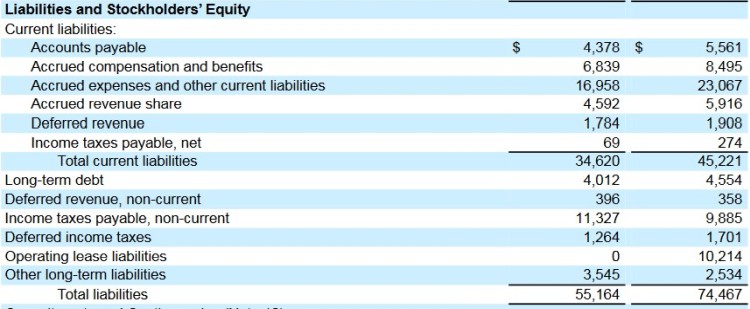

Just like assets, liabilities can be separated into both current and noncurrent liabilities. Current liabilities are liabilities payable within one year, while noncurrent liabilities or long-term liabilities are liabilities payable over a period longer than one year.

The image above represents Google’s fiscal year ended (FYE) 2019 liabilities section of the consolidated balance sheet in their annual report. Accounts payable generally represent the company’s obligation to pay off a short-term debt to its creditors or suppliers.

Another current liability that you may see on the financial statement is trade payables, which represents money a company owes its vendors for inventory related items like materials or business supplies whereas accounts payable includes all of the company’s short-term debts or obligations.

Some other current liabilities you may see broken on the balance sheet include but are not limited to current portions of long-term debt, dividends payable, customer prepayments, wages payable, and interest payable. Management may have the tendency to delay payment of outstanding bills until close to their due date to enhance their cash flow.

When we examine the long-term liabilities section, we will most likely see items such as loans payable, bonds payable, deferred compensation, deferred revenues, deferred income taxes, derivative liabilities, capital leases, pension liabilities, postretirement healthcare liabilities, and customer deposits.

Deferrals

As you may have noticed, the term “deferred” is a pretty popular term in this section. A deferral represents an amount that was paid or received early but the benefits or service to be provided have not occurred yet, so we have to delay or defer the recognition of the associated expense or revenue until it can be recognized in a later accounting period where it can be moved to the income statement.

A brief example would be a company who provides a 3-year subscription for a service, say web hosting. When a customer subscribes and pays the 3-year subscription up front, this revenue would be deferred or postponed until the service is provided by the web host.

The revenue could be recognized on a monthly basis, quarterly basis, annual basis or for the entire 3-year term depending on the rules for revenue recognition for this specific case governed by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) who issue generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).

Liability ordering on the balance sheet

Equity

Equity is basically what we would have left over if we sold all of our assets and paid off all liabilities, where A – L = OE. Equity can be referred to as shareholders’ equity for publicly traded companies or owner’s equity for privately held companies. Shareholder equity can also represent the book value of company and plays an important role in many equations we will explore in future posts.

Stockholders’ Equity = Assets – Liabilities

[common stock + preferred stock – treasury stock] + (net income + other comprehensive income – dividends paid) = [contributed capital] + [retained earnings] = Stockholders’ Equity

The function of equity is to be utilized as capital raised where the company uses these funds to invest in projects, purchase assets, and run the day to day operations. Capital is generated one of two ways, either through the issuance of debt (bonds or loans) and through equity (by selling stock).

When an investor owns stock in the company, they own a piece of that business, they are stakeholders in that business. These investors are paid back through the company growing/expanding, which generates stock appreciation as well as through dividend payments provided by the company, which are simply distributions of a portion of a company’s earnings.

Owning stock or equity in a company will grant these investors the right to vote on elections for the board of directors or on any significant corporate actions (assuming common stock). This feeling of being able to have a direct impact on the company and its decisions enhance shareholders ongoing interest in the company.

Shareholder equity is negative when total liabilities exceeds total assets and if this is the case for an elongated period of time it is referred to as balance sheet insolvency and should be a cautionary sign to be considered when deciding to invest in a particular company.

Components of shareholder’s equity

If that second formula seems confusing, I know it was for me when I first started accounting, this section will make it easier to comprehend! There are six main accounts you will see within the equity section: Common stock, preferred stock, additional paid-in capital (APIC), retained earnings, and other comprehensive income (OCI).

Common stock

As mentioned above, common stock represents owner’s or shareholder’s investment in the company as a capital contribution. Shareholders of common stock are allowed the opportunity to vote. The value of common stock is equivalent to the par value of the shares times the number of shares outstanding.

Par value is simply the stock value stated in the corporate charter. Shares typically either have very low par value or no-par value at all. Par value has no correlation to the shares’ market price. Common names for par value include face value or nominal value.

Preferred stock

Preferred stock behaves very similarly to common stock but there are important differences. Preferred stock does not have voting rights, but they are guaranteed a cumulative dividend. If a dividend is declared but not paid in the first year, then it will accumulate until it is paid off.

Additionally, in the event of company liquidation, preferred shareholders have priority over a company’s income, so they will be paid third (after creditors and bondholders). Common stockholders are the last in line to receive any remaining assets, if any remain after the creditors, bondholders, and preferred stockholders are paid.

Additional paid-in capital

Additional paid in capital or APIC is the value of share capital above its stated par value. APIC is generated whenever a company issues new shares and is lowered when a company repurchases its shares, which are referred to as treasury shares. During an initial public offering, a company is entitled to set any price for its stock that it sees fit.

On the other hand, investors outlook on the price will vary and the market will decide what the initial stock price is for this stock. In this case, if the market views a stock at $31.00 per share at the IPO and the company declared the par value of the stock to be $1.00, the additional paid in capital would be: The market price – par value = $31.00 – $1.00 = APIC of $30 per share issued.

Retained earnings

It brings back nostalgia to discuss retained earnings, because I do remember discussing it quite a bit through my time in school, especially in accounting principles 1 and 2. The retained earnings formula is presented below:

Ending retained earnings = beginning period retained earnings + net income (loss) – dividends paid.

Beginning retained earnings is the ending retained earnings of the prior period which equals the beginning retained earnings of the current period. For instance, ending retained earnings on December 31, 2020 = $100,000. This would carry over to January 1st, 2020 and would be our beginning retained earnings for the current period.

Net income will be described in much greater depth in the income statement blog post, for now just understand that this number represents net income at the end of an accounting period, in this particular example it would be net income as of December 31, 2020. Dividends paid represents all types of dividends including cash, stock, property, and scrip dividends.

Before writing this post, I was not aware of scrip dividends, so I would like to briefly describe this dividend type. Scrip dividends provide the shareholder with the option of either receiving a cash dividend or stock dividend, they have the choice, whereas with a cash or stock dividend, there is not a choice of one or the other.

Other comprehensive income

Other comprehensive includes revenues, expenses, gains, and losses that are not included in net income on the income statement. OCI may have its own statement or be presented after net income on the income statement.

These revenues, expenses, gains, and losses appear in OCI when they have not been realized. Realization occurs when the underlying transaction has been completed and both parties have accomplished their part of the deal.

Some items you may see included within OCI include but are not limited to unrealized holding gains and losses on investments that are categorized as available for sale, pension plan gains or losses, foreign currency translation gains or losses and pension prior service costs or credits.

Company market valuation

Assets – liabilities does equal equity but realistically it does not equate to the company’s fair market value or the value in which someone would purchase the business. A majority of the assets on the balance sheet are recorded at historical cost or the value of the asset at the date the asset was purchased. Fixed assets are recorded at historical cost net accumulated depreciation.

Some items do lose value more than their current depreciation. Examples of such items would be technology such as computers because the hardware is rapidly transforming, and the accumulated depreciation may be understated due to the speed of advancement.

Additionally, a building may have been bought 20 years ago for $500,000 and now has a book value of $100,000. However, that building may now be worth $1,250,000 due to the high real estate demand in the area it is located in where space has become more limited and there is much greater traffic in that area.

Since the items on the balance sheet are not recorded at their current fair market value, stockholders’ equity does not provide an accurate representation of what the fair market value of the business is.

Contra accounts

Before jumping into what the various contra accounts are on the balance sheet it is important to understand that a contra account is any account with a balance that is the opposite of the normal balance. These accounts are used within a general ledger to decrease the value of a related account when the two are netted together.

Accumulated depreciation

For instance, property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) on the balance sheet has a normal debit balance. The contra asset account for PP&E is accumulated depreciation. Accumulated depreciation represents the sum of all recorded depreciation on an asset at a specific date. The carrying value of an asset is equal to the historical cost less the accumulated depreciation.

If a piece of equipment were 30,000 with a useful life of 10 years, assuming straight-line depreciation, the annual depreciation would be 3,000. At year 5, the asset would be reported at 15,000 since 3,000 x 5 = 15,000 of the cost has been allocated or used up as the equipment degrades over time and is reported as a component of accumulated depreciation.

Other types of contra asset accounts include accumulated depletion, allowance for doubtful accounts, obsolete inventory reserves, and discounts on notes receivable. Accumulated depletion is very similar to accumulated depreciation, the only difference is that depletion allocates the cost of extracting natural resources like minerals, timber, oil, etc. from the earth.

Obsolete inventory reserve

Obsolete inventory is inventory that will be written down due to reasons such as spoilage, obsolescence, or theft. The obsolete inventory reserve account is created to account for these instances that inevitably will occur in the future at some point.

Obsolete inventory is a contra account to inventory, so it has a normal credit balance since inventory is an asset. To create this reserve, cost of goods sold is debited by the amount by which someone wants to increase any existing inventory reserve and crediting the inventory reserve account.

Discount on notes receivable

A discount on notes receivable takes place when the present value of the payments to be received from a note is lower than its face amount. The difference between these two values is the amount of the discount.

This difference is progressively amortized over the remaining life of the note, with the offset going to interest revenue. The discount on notes receivable account has a normal credit balance as it is the contra asset account of notes receivable which has a normal debit balance.

Other Assets or Liabilities

When examining a balance sheet, sometimes you will see two unique line items: other assets or other liabilities. These items represent miscellaneous items that cannot be classified into the other categories listed on the balance sheet. I do not know about you, but I do not like the vagueness attached to these accounts.

My personal advice to you is if you see these accounts on a balance sheet you are examining, I would encourage you to check out the footnote disclosures that will provide you some further details over what is included in these accounts to resolve some of that ambiguity.

Weaknesses of a balance sheet

Financial Snapshot

Nothing is made perfect and it is essential to understand some of the drawbacks of the balance sheet. The first weakness of a balance sheet is that it is a financial snapshot at a specific point in time.

It does not account for what is going on in the present (assuming the present is at some point after the reporting date). This static image of what is going on at a specific point in time does not consider the long-term prospects of the business.

As an example, a company may have acquired more debt and decreased their liquidity on the balance sheet but behind the scenes they are spending a lot of money on research and development and are on the verge of releasing a product or service that will massively improve their revenues/efficiencies in the future.

Improper valuation on long-term assets

Second, a balance sheet may have improperly valued long-term assets. Depreciation is an estimate of wear and tear of assets and is based off a schedule generated in software for tax purposes but sometimes does not accurately reflect the real wear and tear on equipment.

Sometimes the method of depreciation the company uses also makes it harder to have an apple to apple comparison with its competitor because they use a different depreciation method as there are four to choose from.

Further, the cost of replacing a long-term expensive asset can become distorted because the asset is reported at historical value and is reported net of depreciation. An asset with the same functionality may cost a lot more today to reacquire.

Limited to transactional reporting

Third and most importantly, the balance sheet only reports assets that were acquired through transactions. Therefore, the balance sheet does not include some very essential assets that are not transaction based and cannot be expressed in monetary terms.

Some of these assets may include excellent leadership within the company, a strongly desired company culture, staff with adept knowledge that would be difficult to replace, and employee loyalty/honesty.

Balance sheet’s connection with other financial statements

The order in which financial statements are prepared are as follows from first to last: the income statement, statement of stockholders’/owner’s equity, the balance sheet, and the cash flow statement.

When the income statement is prepared, we take the net income from the bottom of the income statement and that is directly linked into retained earnings and for the cash flow statement net income is placed at the top of the cash flows from operating section assuming the more prevalent indirect cash flow method.

Fluctuations in values on the balance sheet when comparing the previous period balance sheet and current period balance sheet is necessary data for the cash flow statement. For instance, a decrease in accounts receivable (receipt of payment on items customers bought on credit) would be a cash inflow and would be present in the cash flow from operations section.

Depreciation expense is taken from the income statement and netted out of the balance sheet PP&E account. Depreciation and other capitalized expenses on the income statement are also needed to be added back to net income to calculate cash flows from operations as depreciation/amortization/depletion expense are noncash expenses.

Capital expenditures are added to the property, plant and equipment account on the balance sheet and flow through cash from investments on our cash flow statement. I totally understand if this section seems more confusing, when the income statement and cash flow statement posts are available, it will make a lot more sense!

I used to proofread financial statements and one of the steps I would take is to sum cash flows from operations, investing, and financing activities and add this sum to the prior period cash balance to arrive at our current end of period cash balance. If this cash balance ties to the cash balance presented on the balance sheet, then it is a great sign that our balance sheet balances properly!

Cost Principle

The cost principle is one of the more important principles in accounting laid out under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). It requires that assets be recorded at their cost the day they were acquired. This principle is also referred to as the historical cost principle. The asset value is also not permitted to change for inflation or improvements/reductions in market value.

The cost principle does not permit an organization from recording an asset that was not acquired in a transaction as we had discussed earlier in the drawbacks of the balance sheet. One of the exceptions to this rule is the fluctuation of market value for short-term investments, which are recorded at their fair value on the balance sheet.

These short-term investments are any investment made with the anticipation of selling the investment in one year or less. A second exception is that impaired assets may be written down to fair market value if their fair market value is less than the historical cost, this is the accounting principle conservatism in play.

This cost principle assists in making comparisons between two companies in the same industry easier as they will both value a majority of their balance sheet accounts at historical cost.

Off balance sheet accounts

What is allowed and disallowed to be recorded off the balance sheet is changing quite frequently with new GAAP standards generated by FASB, as they are attempting to minimize off balance sheet reporting.

At a very high level, off-balance sheet refers to assets or liabilities that are not present on an organization’s balance sheet. These items are usually not owned by or a direct obligation of the organization.

These items typically are associated with the sharing of risk or they are financing activities. Companies may attempt to utilize off balance sheet accounting to make their balance sheets appear stronger/healthier (higher liquidity and less debt/leverage).

Companies make it possible to get these assets or liabilities off the books by entering into transactions that are created to transfer the legal ownership of transactions to other entities. It is essential to note that even though these assets or liabilities do not show up on the balance sheet, they will be disclosed in the notes to the financial statements.

Some common off-balance sheet items that you may run into include but are not limited to operating leases, leaseback agreements, and accounts receivable.

I imagine there may be some confusion over why a company would want their accounts receivables off the books (exchanged for partial cash payment), especially since it is in asset.

Accounts receivable are amounts due from customers for credit purchases, there is a possibility that the customer will not pay the balance (default).

The company may view this as a more risk-laden asset, and they do have the ability to sell their A/R to another company. The company in which they sell the A/R to is referred to as the “factor.”

Once the A/R is sold, the company that bought the A/R acquires the risk associated with this asset.The factor does not buy the A/R at the full A/R amount, they usually pay the company a percentage of the total value of all A/R upfront and take care of the collection process.

Once the company that purchased the A/R receives money from customers, the factor will pay the company that sold the A/R the balance due less a fee for services provided.

Utilizing this strategy, the company can collect what is owed to them while outsourcing the risk of default.

Commitments and contingencies

When scrolling through the balance sheet, you may see a line at the end of the liabilities section or between the liabilities and the equity section named “Commitments and Contingencies.”

This line may or may not have an associated balance, rather its primary purpose is to guide you to the footnote disclosures where the company will detail out any commitments or contingencies the company has typically as of the balance sheet date.

Some examples of a commitment you might see on the balance sheet include a building or machinery lease or even a contract to buy equipment or inventory in the future. The lease itself is a commitment to pay future amounts to the lessor.

A contingency is a future event or circumstance which is possible but cannot be predicted with certainty. Contingencies can be presented on the balance sheet if two conditions are met: The amount of the loss must be reasonably determinable, and the probability of a loss or claim has to be greater than 50%.

There are two forms of contingencies: gain contingencies and loss contingencies. A gain contingency is created if the outcome of future events may result in a gain or benefit to an entity through an increase to assets or a decrease in liabilities and a loss contingency is just the opposite.

We really just scratched the surface when it comes to commitments and contingencies to achieve a basic understanding, if you would like to read more about this topic WallStreetMojo has a much more in depth article about commitments and contingencies.

Closing engagement

I hope that you enjoyed reading this article and that the headline lived up to expectations! I would like to use this final section of the post to engage with you. What did you think about the post? Was there any information that you were looking for about the balance sheet that was not present? Did the structure of the post provide a good reading experience?

In the present and moving forward, reader experience will be very important. The posts will be informative, but I also want to ensure that the paragraph structure, image flow, style, and appearance of writing are optimized to keep you engaged to soak up the content and improve the learning experience. I am looking forward to viewing your comments in the future!